I. Introduction

Numerous automobile manufacturers and technology companies are developing automated driving systems. Every year these companies come out with new technologies that seek to reduce the “human factor” in driving. These companies all share the same goal: fully autonomous vehicles (AV).

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s 2018 annual report, approximately 37,000 people died in motor vehicle collisions that year and another 2.7 million were injured. The United States Department of Transportation estimates that human error accounted for 94% of these crashes. These statistics are widely cited by advocates of AV technology, and it is easy to back a cause that may eliminate 94% of unnecessary injuries and deaths. However, along with potential benefits, one can also perceive the inevitable problems, especially in the legal sector. How do we regulate AV? Who will be at fault in the event of a collision? How will an injured party recover their damages?

II. Levels of Automation

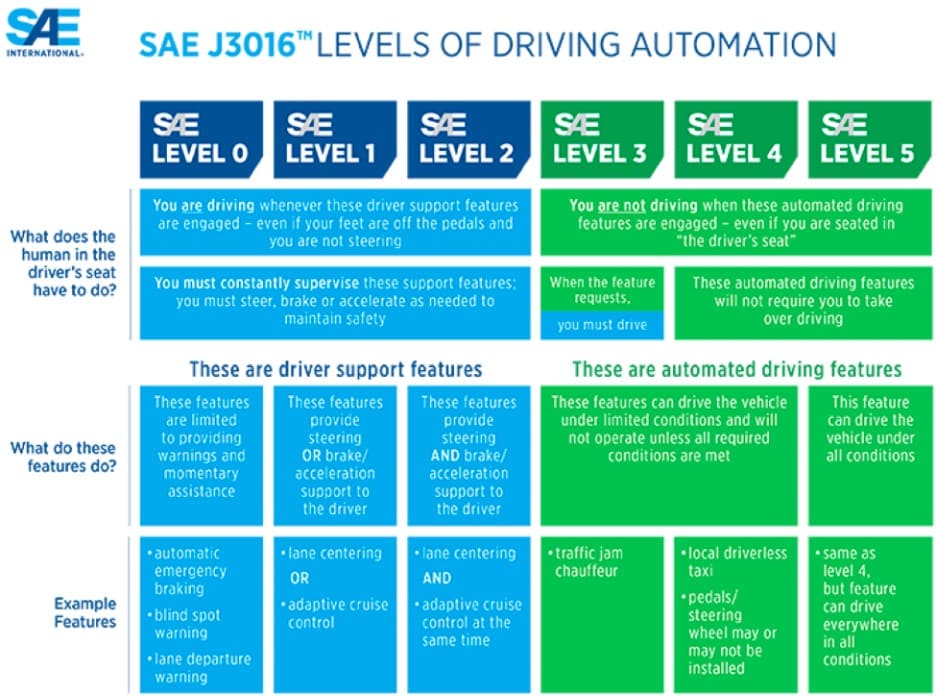

The U.S. Department of Transportation adopted the Society of Automotive Engineers’ (SAE) six-level classification of driving automation. This classification scheme is currently accepted across government and industries.

As outlined below,1 “Automated Driving” (SAE levels 3-5) are vehicles that do not require human input to safely operate. Some examples include robotaxis, automated buses, automated trucking, and autonomous personal use vehicles. Currently, vehicles are being developed that qualify as Level 4, but they are not yet available to the general public.

“Manual Driving” (SAE levels 0-2) vehicles are currently available to the general public. SAE Levels 0-2 are not fully autonomous and require a human driver to monitor the driving environment and be ready to take control at any moment to ensure safety.2 The most advanced manual vehicles (Level 2) are equipped with driver assistance systems that allow the vehicle to control both steering and braking/accelerating simultaneously without human input. These technologies include automatic emergency braking, adaptive cruise control, lane keeping, and limited “autopilot.”

A widespread misconception exists regarding the AV technology currently available. This is due in part to corporate advertising. Probably the most well-known manufacturer in the industry, Tesla, stated in a press release in 2018 that all of its vehicles were equipped with technology to make them “self-driving,” and “they are safer than human drivers.”

However, Tesla autopilot technology requires human control (Level 2). As discussed below, this misunderstanding of the technology led to a class action lawsuit against Tesla. Corporate “misrepresentation” was also alleged in litigation concerning two motor vehicle fatalities involving a Tesla vehicle.

Practice tip: Identifying the level of automation is important when assessing liability and determining what legal claims to plead. However, the six level SAE classification system may confuse a jury. It may be more straightforward to frame the discussion as “Manual Driving” (Levels 0-2) vs. “Automated Driving” (SAE Levels 3-5).

III. AV Incidents & Litigation

There has not been significant litigation surrounding AV, and the litigation in existence is in its infancy. What follows are summaries of some of the incidents and litigation we located across the country involving AV.

On June 29, 2016, Josh Brown was killed when his Tesla vehicle operating in autopilot collided with a white truck in Williston, Florida.3 This was the first U.S. death involving a vehicle operating with autonomous features engaged. Tesla’s autopilot did not detect the white truck that “drove across the highway perpendicular to the Model S” before the accident. Tesla admitted that “neither autopilot nor the driver noticed the white side of the tractor trailer against a brightly lit sky, so the brake was not applied.” The National Traffic Safety Board (NTSB) concluded the probable cause of the accident was “the truck driver’s failure to yield the right of way and a car driver’s inattention.” Importantly, NTSB also concluded Mr. Brown’s pattern of use of the autopilot system showed an “over-reliance on the automation and lack of understanding of the system’s limitations.”4

In Nilsson v. General Motors LLC, Nilsson was injured when a “selfdriving” Chevrolet Bolt suddenly changed lanes and collided with his motorcycle.5 There was a human driver in the Bolt at the time of collision, but he did not have his hands on the wheel while its autonomous mode was engaged. On January 22, 2018, Nilsson filed a complaint in federal court in California alleging negligence by General Motors. The claim was settled six months later for an undisclosed amount.

In Hudson v. Tesla, Inc., Hudson alleged his 2017 Tesla Model S failed to detect the presence of a disabled vehicle on the roadway, causing a collision at approximately 80 miles per hour.6 Hudson pled the following counts against Tesla: (1) strict liability; (2) negligence; (3) breach of implied warranty of fitness; (4) misrepresentation; (5) misleading advertising; and (6) unfair and deceptive trade practices. Hudson also alleged negligence against the owner of the abandoned vehicle.

On March 18, 2018, a fatal motor vehicle collision occurred in Tempe, Arizona, involving a self-driving Uber vehicle. The Uber vehicle was outfitted with a “sensing system,” and was in autonomous mode with a human driver when it struck Elaine Herzberg.7 NTSB concluded that the Uber SUV could not determine whether Herzberg was a pedestrian, vehicle, or bicycle, and it also failed to correctly predict her path. Specifically, “the system design did not include a consideration for jaywalking pedestrians.”8 At 1.2 seconds before the collision, the system identified Herzberg as a bicycle moving into the path of the Uber but it was too late to brake or avoid a collision. Interestingly, in 2015, Arizona governor Doug Ducey used an executive order to declare Arizona a regulation-free AV zone in order to attract testing operations from companies like Uber.9

In Lommatzsch v. Tesla, Inc., Lommatzsch had engaged her Tesla Model S autopilot when the car slammed into another vehicle at 60 mph.10 Lommatzsch alleged that Tesla’s sales staff assured her the Model S would “stop on its own in the event of an obstacle being present in the path of the Tesla Model S.” According to the lawsuit, Tesla was “negligent in developing, designing, manufacturing, producing, testing, promoting, distributing, selling, maintaining, repairing, and/ or servicing the Tesla Model S, and/ or providing adequate warning of the dangers of the Tesla Model S.”

On May 24, 2018, Tesla settled a class action lawsuit with buyers of its Model S and Model X cars who alleged that the company’s autopilot system was “essentially unusable and demonstrably dangerous.”11 The plaintiffs argued they became “beta testers of half-baked software that renders Tesla vehicles dangerous,” and that when autopilot is engaged, it is susceptible to “lurching, slamming on the brakes for no reason, and failing to slow or stop when approaching other vehicles.”

In Huang et al, v. Tesla, Inc., the estate of Wei Huang sued Tesla after Huang’s Tesla drove into a concrete median while engaged in autopilot, causing his death in March 2018.12 Huang’s claims against Tesla included negligence, wrongful death, strict liability, negligence (post-sale), defective product design, failure to warn, intentional and negligent misrepresentation, and false advertising.

On March 1, 2019, Jeremy Banner was killed when he collided with a tractor trailer in Florida. Preliminary data from the vehicle showed that his Tesla’s autopilot system was engaged approximately 10 seconds before the collision, that neither Banner nor the autopilot slowed the car or attempted any evasive maneuver and that the vehicle did not detect the driver’s hands on the steering wheel.13 Banner’s estate alleged false advertising of the 2018 Model 3. The ad in question stated that “if you have purchased the optional Enhanced Autopilot or Full Self-Driving Capability Package, the forward looking cameras and the radar sensor are designed to determine when there is a vehicle in front of you in the same lane. If the area in front of Model 3 is clear, traffic-aware cruise control maintains a set driving speed. When a vehicle is detected, traffic-aware cruise control is designed to slow down Model 3 as needed to maintain a selected timed based distance from the vehicle in front, up to the set speed.”14

Practice tip: Electronically Stored Information (ESI) is a key component in every AV lawsuit. It is extremely important to preserve the vehicle, and all for ms of ESI, including from periphery devices, such as cell phones and laptops. Virtually all incidents referenced above included ESI. In the Herzberg collision, ESI included data from the car as well as a dashcam video showing the driver repeatedly looking down at her lap. In the Banner collision, ESI confirmed Banner turned on autopilot seconds before the crash, and the vehicle did not detect Banner’s hands on the steering wheel. In the Brown collision, ESI detected a pattern from the driver while in autopilot, which underpinned NTSB’s conclusion that he did not fully understand the technology.

IV. Legislation Regarding AV

As technological advances continue, so will legislation and regulatory standards. While the federal government is responsible for setting motor vehicle safety standards, states remain the regulatory body for licensing, registration, law enforcement, insurance, and liability.

Numerous states have enacted legislation regarding AV. Generally, these laws pertain to vehicle automation at Levels 3 and 4 and involve licensing requirements including greater liability insurance coverage. In addition, governors in 11 states15 have issued executive orders related to autonomous vehicles. Montana does not currently have any form of AV regulation.

Congress also proposed several regulatory frameworks, including the Safely Ensuring Lives Future Deployment and Research in Vehicle Evolution (SELF DRIVE) Act in the House, and the American Vision for Safer Transportation through Advancement of Revolutionary Technologies (AV START) Act in the Senate. However, both the SELF DRIVE Act and the AV START Act stalled in the Senate in 2018. It appears that there is ongoing bipartisan support for AV legislation. This includes the establishment of a “Highly Automated Vehicle Advisory Council” within the Department of Transportation (“DOT”) to evaluate issues related to AV and address federal regulation of AV testing.

On March 23, 2018, President Trump signed into law the Consolidated Appropriations Act (2018 Omnibus Bill). This legislation, among other things, directs the DOT to conduct research on the development of AV. On April 16, 2020, DOT and the White House Office of Science and Technology published the Ensuring American Leadership in Automated Vehicle Technologies: Automated Vehicles 4.0, which provides recommendations for state legislation.

V. Legal Framework

It is not certain how AV litigation will unfold. Who will be responsible for a car’s “negligence”? The car manufacturer? The maker of the automation component parts, such as sensors, cameras, or navigation systems? The person who was in the driver’s seat but not actually driving? All three? Will there be statutory limitations and/or claims?

Several theories exist concerning how courts should address AV liability. David King proposes to analogize AV liability with the way courts handle accidents involving equine transportation. Both horses and selfdriving vehicles can perceive their environment, misunderstand their surroundings, and make dangerous maneuvers independent of their human operator’s will.16

For example, in Alpha Construction v. Brannon, 337 SW2d 790 (Ky. 1960), a horse walking on the side of a road was startled by a loud noise and galloped into the street, causing an accident. In comparison, in the 2016 Tesla fatality discussed above, the AV “saw” a white truck against a bright sky, thought it was not dangerous and drove straight into the truck. The resulting maneuvers in both circumstances were caused by a lack of understanding of the surroundings. Further, both horses and AVs are property, owned and operated by regular consumers who can lend them to others.

Another theory encourages lawmakers to adopt a strict liability standard against the industry for accidents involving AV based on the dangerous instrumentally doctrine. Proponents argue that AVs are more hazardous than ordinary cars, so strict liability standards should be applied, similar to early aviation cases.17 It remains uncertain what liability standards will actually apply.

The urgent question is how liability will be addressed as society transitions to fully automated vehicles. During this period, humans and varying levels of AV will share the roads as well as the duty to drive in a safe and reasonable manner. Under general tort law principles, the element of control will typically be determinative. The question of how much control the driver had, or should have had, at the time of the accident will determine whether the driver could have prevented the accident.

Traditionally, motor vehicle collisions are assessed according to driver negligence, with the potential for product liability when a defect in the car causes the accident or exacerbated the injuries. The few incidents to date nearly all involved negligence allegations, suggesting a wholesale shift to products liability is unlikely. This seems especially true during the long time period during which manual, semi-autonomous, and fully autonomous vehicles share the roadway.

Based on the incidents to date, there generally seems to be three different liability avenues in AV cases: (1) product-based theories; (2) corporate activity theories; and (3) drivingbased theories.

Product-based theories include “strict” product liability (consumer expectations test, risk/utility, reasonable alternative design), warranties in the form of marketing or other representations promising reasonable safety, and strict liability for the owner of the AV.

Corporate activity theories include negligence in product design, common carrier duty of care, ultrahazardous activity, engineering malpractice, misrepresentation, and false advertising.

Driving-based theories include actions against the negligent driver and/or the company with control over the automated driving system at issue. For the time being, we anticipate plaintiffs will continue to employ a hybrid approach naming multiple defendants and multiple allegations in AV litigation.

We anticipate insurer/manufacturer defenses to include: (1) assigning liability to the driver and/or injured party; (2) claiming the accident was unavoidable; (3) denying the existence of a defect; and (4) relying on “industry standards,” as these are only starting to develop, no regulatory framework exists, and much of the technology is labeled “trade secret.”

VI. Ethical Dilemmas of AV

Fully autonomous vehicles will become a reality. It is also likely that AV will not completely eliminate collisions. When collisions occur, their outcomes may be predetermined by programmers and policy makers.

Many ethical dilemmas surface when predetermining the outcome of collisions, which trial lawyers need to understand. For example, pretend you are driving an AV on a busy highway boxed in by other vehicles. Suddenly, a large object falls off the truck in front of you. Your car cannot stop in time, so it makes one of three decisions: (1) go straight, brake, and hit the object; (2) swerve left and hit a vehicle; or (3) swerve right and hit a motorcycle.

Should the AV prioritize your safety by hitting the motorcyclist? Minimize harm by going straight and hitting the large object, even if that means maximizing harm to you? Or take the middle road and hit the SUV on your left which has a high passenger safety rating?

If a human was driving, the human’s reaction would be chalked up to just that: a reaction. However, with AV, there are no reactions, only programmed decision-making. These decisions are the result of algorithms that, by design, determine the most favorable collision. In other words, the vehicle systematically favors a certain type of crash. The passengers of this algorithmic decision will suffer the consequences.

Should fault play into the programming? Further, who should be making these decisions? Engineers, corporate boards, or legislators? Watch this short TedTalk video for an interesting discussion regarding ethical dilemmas with AV.18 VII. Conclusion Victims of motor vehicle injuries will be faced with new and challenging issues as AV technology races forward. These technological advancements will undoubtedly provide corporations and insurers with new and sophisticated methods to shift blame, avoid responsibility, and deny injury victims full legal redress. Those injured by AVs will need attorneys familiar with the issues to pursue their claims. Attorneys will also need to work with lawmakers to ensure technological advancements do not swallow the guarantees within Article II, Section 16 of Montana’s Constitution.

END NOTES

- https://www.sae.org/news/ press-room/2018/12/sae-international- releases-updated-visual-chart-forits-% E2%80%9Clevels-of-drivingautomation% E2%80%9D-standard-forself- driving-vehicles

- https://www.nhtsa.gov/technologyinnovation/ automated-vehicles-safety

- https://www.tesla.com/blog/tragicloss

- https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/ AccidentReports/Reports/ HAR1702.pdf

- Oscar Nilsson v. General Motors LLC, Case 4:18-cv-00471-KAW, United States District Court Northern District of California (2018).

- Hudson v. Tesla, Inc., et al, Circuit Court 9th Jud. Circuit, FL (2018).

- https://www.nytimes. com/2018/03/19/technology/uberdriverless- fatality.html.

- https://www.documentcloud.org/ documents/6540547-629713.html

- Arizona Executive Order 2015-09, “Self Driving Vehicle Testing and Piloting in the State of Arizona.”

- Heather P. Lommatzsch v. Tesla, Inc., et al., Third District Court for the State of Utah, Salt Lake County (2018)

- https://www.reuters.com/article/ us-tesla-autopilot-lawsuit-idUSKCN1IQ1SH

- Szu Huang et al, v. Tesla, Inc., dba Tesla Motors Inc., et al, Case No. 19-CV- 346663, Superior Court of the State of California (2019).

- https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/ AccidentReports/Reports/ HWY19FH008-preliminary.pdf

- Kim Banner, as Personal Representative of the Estate of Jeremy Banner, v. Tesla Inc., et al., 15th Judicial Circuit for Palm Beach County Florida (2019).

- https://www.ncsl.org/research/ transportation/autonomous-vehiclesself- driving-vehicles-enacted-legislation. aspx

- Putting the Reins on Autonomous Vehicle Liability (North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology, Vol. 19, December 2017)

- Adam Rosenberg. Strict Liability: Imagining a Legal Framework for Autonomous Vehicles. Adam Rosenberg, Volume 20, Tulane Journal of Technology (July, 2017).

- https://www.ted.com/talks/patrick_ lin_the_ethical_dilemma_of_self_ driving_cars