In a 4-3 decision in Hensley v. State Fund, 2020 MT 317, the Montana Supreme Court held that the provisions of Mont. Code Ann. § 39-71-703(2) (2011) disallowing impairment awards to injured workers with a Class 1 impairment and no wage loss did not violate Equal Protection. The 78-page decision, decided nine years after the claimant was injured, is another sign of Montana’s trend to erode the rights of injured workers. However, Hensley also provides insight on the future of constitutional challenges in Montana.

Hensley arises from the 2011 Legislative overhaul of the Workers’ Compensation Act (“Act”), which added language denying indemnity benefits to workers with a Class 1 impairment and no wage loss. The statutes before and after the 2011 change read as follows:

Mont. Code Ann. § 39-71-703(2) (2009)

When a worker receives an impairment rating as the result of a compensable injury and has no actual wage loss as a result of the injury, the worker is eligible for an impairment award only.

Mont. Code Ann. § 39-71-703(2) (2011)

When a worker receives a class 2 or greater class of impairment as converted to the whole person, as determined by the sixth edition of the American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment for the ratable condition, and has no actual wage loss as a result of the compensable injury or occupational disease, the worker is eligible to receive payment for an impairment award only.

Impairment percentages are assigned according to the American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 6th Ed. (“Guides”). Interestingly, before the 6th Edition of the Guides was published in 2008, “Classes” did not exist, only percentages.

The Montana Legislature incorporated the 6th Edition into the Act, which paved the way for the “Class 2 or greater” language that was challenged in Hensley. Historically, all impairments were paid. The idea of only paying some impairments was pitched as a novel way to reduce workers’ compensation premiums. The proposed rationale behind the denial of Class 1 impairment benefits was the Legislature’s understanding that Class 1 impaired workers are categorically less injured than Class 2 impaired workers. Sadly, this is simply not true in all circumstances.

I. A Recap of Hensley

Hensley brought a facial challenge against Sec. 703(2), arguing that the denial of Class 1 impairment benefits was an unconstitutional violation of Equal Protection under Mont. Const., Art. II, § 4, which states, “No person shall be denied the equal protection of the laws.”

The Equal Protection legal analysis is a three-step process:1

- First, the court decides whether the statute creates two similarly situated classes.

- Second, the court determines the appropriate level of scrutiny.

- Third, the court analyzes the statute under the appropriate level of scrutiny.

The Hensley court agreed the statute created two similarly situated classes. The court also applied the “rational basis” analysis, which has historically been used in challenges to workers’ compensation laws.2

Hensley’s fundamental argument was that an injured worker is either permanently impaired or not. If permanently impaired, they should receive an impairment benefit. Claimants with a lower impairment percentage receive a smaller award, whereas those with a higher impairment percentage receive a greater award. Hensley contended that to deny benefits categorically to some impaired workers is irrational as the “Class” distinction within the Guides is an arbitrary line.

The Hensley court upheld the Class 1 denial of benefits under the rational basis test. In summary, the court held:

- “[T]he government has a legitimate interest in providing benefits that bear a reasonable relationship to the actual functional loss a worker sustains.”3

- “The Legislature rationally could decide that claimants with a Class 2 or higher impairment rating are more likely to have sustained the loss of functionality that impairment awards are meant to compensate.”4

Unfortunately, the Hensley court made the same erroneous assumption as the Legislature – that a Class 2 impairment is worse than a Class 1 impairment. While incorrect, the notion was apparently “rational enough” to pass constitutional muster in the court’s eyes.

II. Future Challenges to the Denial of Class 1 Impairment Benefits

A. “As-Applied” Challenges

Having brought a facial challenge against Sec. 703(2), Hensley bore the heavy burden of proving that “no set of circumstances exists under which the statute would be valid.”5

While the court upheld the constitutionality of the statute, even the majority left the door open to an “as-applied” challenge:

A worker whose injury and whole person impairment percentage result in a Class 1 impairment could bring an as-applied challenge if the worker claims to have suffered a significant functional impact or injuries to multiple organ systems not accounted for in the Class designation.6

While Footnote 10 invites an “as-applied” challenge, the court’s use of the word “significant” is perplexing. The Guides specifically define every “impairment” (including Class 1) as “[a] significant deviation, loss, or loss of uses of any body structure or function in an individual….” and the court cites this definition.7

By definition, all impairments are “significant.” The court’s use of the word “significant” can only be interpreted to mean that future as-applied challenge may require a showing by the injured worker that their injury is “more significant” than other “significant” Class I impairments. The conundrum found in Footnote 10 is common with legal challenges utilizing the rational basis standard. Courts employing rational basis often engage in semantic gymnastics as they search for ways to uphold the constitutionality of legislative enactments.

In any event, there are many instances in which the functional effect of a Class 1 impairment is demonstrably more significant than a higher-Class impairment. Practitioners should be on the lookout for the following:

1. A Claimant with Multiple Class 1 Impairments to Multiple Organ Systems

The Guides do not allow multiple Class 1 injuries to combine to reach an overall Class 2 whole person impairment.8

Consider a construction worker who falls from scaffolding and injures multiple body parts (spine, upper extremities, lower extremities, internal organs, etc.). That injured worker may sustain multiple Class 1 impairments to multiple body parts, so the combined value of the Class 1 impairments may reach a significant overall impairment percentage. While the Guides have a formula to combine impairment percentages, it does not have a formula to allow multiple impairments to graduate into higher Class of impairment. Therefore, an injured worker with multiple injuries is objectively more injured and impaired and has lost more functionality than many Class 2(+) impairments. However, absent an “as-applied” finding of unconstitutionality, such an injured worker gets nothing.

Injuries to multiple organ systems are not entirely uncommon. The authors have handled similar cases that ultimately settled, ostensibly because the insurer also recognizes the problem with Sec. 703(2) in such a context. The difficulty with the rational basis test as set forth in Hensley is there is no way to know when a person with multiple Class 1 impairments is hurt “significant[ly]” enough to offend the judge’s sensibilities. Is a person with three Class 1, 4% impairments hurt enough? What about two Class 1, 8% impairments? Regardless, these examples expose the absurdity of the Class scheme as utilized by Sec. 703(2).

2. Some Impairments Do Not Have a “Class”

Some conditions result in impairments which do not even have a class under the Guides, only a whole person impairment percentage:

- Mental Impairments9

- Digital Nerve10

- Hearing loss11

Under the court’s decision in Hensley, it is unclear how these impairments should be treated. Obviously, the argument should be made that a denial based on Class is impossible, inapplicable, and unconstitutional.

3. A Class 1 Impairment with greater than Class 1 Impairment “Factors”

According to the Guides, Classes range from 0-4, extending from no impairment to a very severe impairment. (0=none; 1=mild; 2=moderate; 3=severe; 4=very severe). The higher the Class, the greater the impairment; but there is a catch: there are multiple “class” designations for each impairment.

Some Class 1 impairments can have three of the four medical factors that would raise the rating to Class 2 status, but the “key factor” robs them of Class II designation. This problem of disproportion argument is logically strong but also gets into the weeds regarding the medical science of the Guides. In retrospect, this was perhaps the biggest obstacle in bringing the constitutional challenge to Sec. 703(2). In short, there is very much a dispute about what the “Class” designation represents. What follows is a brief explanation of how “Class” is rendered; however, please refer to the Hensley briefing for a more thorough explanation.

Per the Guides, Impairments are comprised of four distinct medical factors.

- History of Clinical Presentation

- Physical Findings

- Clinical Studies or Objective Test Results

- Functional History or Assessment

The impairment examiner must individually assess and rate each factor to reach the final whole person impairment percentage. However, for every injury, only one of the four factors is deemed the “key factor.” The key factor is typically the “History of Clinical Presentation.”12

The remaining three factors are relegated to become “non-key factors.”13

Thus, the “key factor” alone determines the final impairment “Class” for purposes of Sec. 703(2).

All four factors are assigned a distinct “Class” of severity, but only the “key factor” determines the

“Class” of impairment. Specifically, a “mild” finding in clinical presentation does not mean the other three factors are mild. The other three factors may range from 0-4, so the key factor may distort the impairment’s ultimate “Class.” The same condition could be Class 2 or higher if the other three factors were given equal consideration. For example, an injured worker with a Class 1 “History of Clinical Presentation” may have a more severe Class 3 “Functional History” rating, so the resulting Class 1 impairment tells us absolutely nothing about this claimant’s loss of function.

Hensley’s invitation to bring “as-applied” challenges may allude to claimants with Class 1 overall impairments who have a Class 2 (or greater) “Functional History” factor. Maybe such a circumstance would increase to “significant” in the court’s eyes.

Take a closer look at impairment ratings for Class 1 injured clients. There are four distinct classes, sometimes also referred to as “grade modifiers.” If a claimant with a Class 1 impairment has a Class 2(+) for any of the other three factors, an argument can be made that person is not Class 1, or, that person is unconstitutionally denied equal protection, as-applied.

4. Class 1 Impairments can be Equal to or Greater than Class 2 Impairments

Oddly, Class 1 impairments are not necessarily less than Class 2 impairments. Per the Guides, the Act, and the court, the ultimate measure of impairment is whole person percentage.14

Impairment percentage indicates the severity of an injury, Class designation does not. There is no legitimate dispute that an injured worker with a 10% impairment is more impaired than an injured worker with a 6% impairment, regardless of Class.

There are countless examples in the Guides of Class 1 impairments that have a higher impairment percentage than Class 2 impairments. This absurd result is again caused by the application of the “key factor” method discussed above.

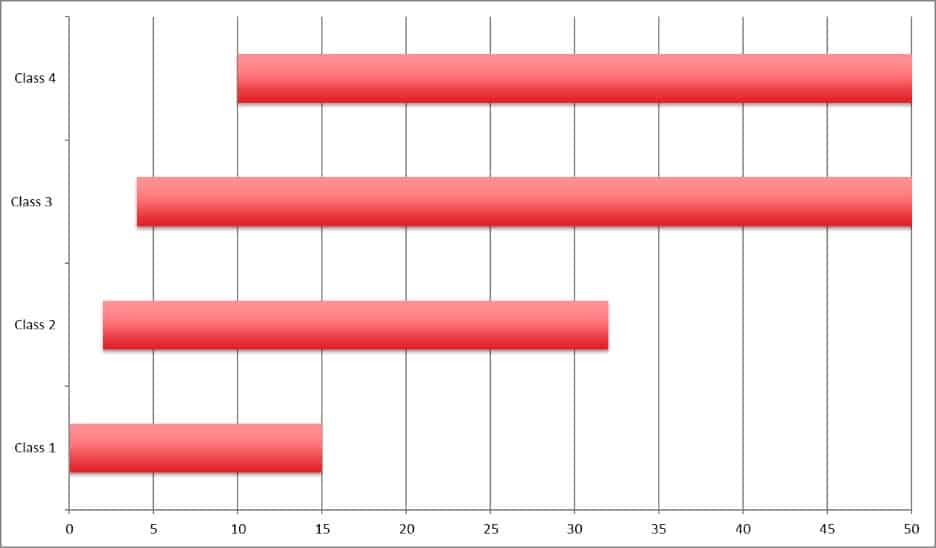

Notes:

Class 1: 1% – 15% (pg. 209, Leukemia)

Class 2: 2% (pg. 344, Miscellaneous peripheral nerves) – 32% (pg. 134, Urinary tract disease)

Class 3: 4% (pg. 344) – 65% (pg. 204, Hemophilias)

Class 4: 10% (pg. 220, Pituitary disorder) – 100% (pg. 327, consciousness and awareness)

The chart above illustrates the significant overlap of impairment percentages within the four impairment Classes for various injuries.

Hensley supplied the court with this chart showing the range of impairment percentages for each “Class” to illustrate the massive overlap. In fact, for every single Class 1 impairment percentage, except for 1%, there is a corresponding impairment rating of the identical percentage that is Class 2, or greater. Thus, for every claimant with a Class 1, 2%-or-greater impairment who is denied payment, it can be conclusively said that another claimant with an equal or lower impairment receives an impairment award.

Sec. 703(2) is a statutory scheme that often denies impairment benefits to people who are equally or more impaired than others with Class 2 impairments – an absurd result. An “as-applied” challenge, with specific focus on comparing a Class 1 impairment with Class 2 impairment of lesser percentage, may be successful.

B. Due Process – The Hensley Dissents

Though no real consolation, the Hensley decision was close. The 4-3 decision had two lengthy dissents and one short concurrence. In the authors’ opinions, Justice Gustafson’s dissent properly analyzed the Equal Protection violation.15

Justice Sandefur’s dissent, joined by Justices Gustafson and Fehr, is interesting as it seems to invite a Due Process challenge by focusing heavily on the quid pro quo foundation of the Act.16

While a quid pro quo analysis is typically reserved for a Due Process challenge, Judge Sandefur unmistakably weaved the quid pro quo issue into an Equal Protection framework. Thus, Justice Sandefur’s dissent gives rise to questions and, potentially, opportunity. The Montana Supreme Court has struck down numerous workers’ compensation laws under Equal Protection without the need to overtly rehash the underlying quid pro quo foundation of the Act.17

Judge Shea specially concurred mentioning Judge Sandefur’s quid pro quo discussion. However, Judge Shea’s analysis does not track prior Equal Protection constitutional precedent, focusing instead on Due Process. It is difficult to know whether these opinions move the goal posts closer to the injured worker in future Equal Protection challenges.

While there is room for a Due Process challenge, beware of Walters v. Flathead Concrete Products Inc.18

In Walters, the court held that $3,000 was enough for a work-related death, even though the person gave up the right to wrongful death and survivorship actions under quid pro quo.

III. Is Rational Basis a Door Mat?

Hensley may have been foreshadowed long ago when a police officer watched a 17-year girl slowly die from suicide. The officer was clearly traumatized, lost his job, and yet he was denied workers’ compensation benefits. There, the court “rationalized” benefit denial, and Justice Trieweiler passionately dissented:

The majority opinion is the best example yet for the belief by many constitutional scholars that the “rational basis” test is no test at all.

… In recent years in Montana, no group has had less political influence and been the subject of more political demagoguery than those unfortunate people injured and disabled during the course of their employment. No group has had greater influence than those employers, led by the State’s newspaper publishers, who consider injured workers an unnecessary business expense and an obstruction to the ever elusive “better business climate” that they seek for the State of Montana.

Sadly, today’s decision by the majority sounds the death knell for this critical constitutional protection which powerless people have traditionally relied on courts to enforce.

Based on the majority’s decision in this case, discriminatory laws in Montana need have no rational basis in fact so long as a majority of the members of this court can contrive some speculative basis to support such discrimination.19

It is hard not to agree with Justice Trieweiler. The Hensley decision is based on vague language that the Legislature “could decide” it is “more likely” that someone with a Class 2 impairment is more hurt than a Class 1, despite the fact that the Guides denounce this conclusion, and the legislative materials make no such mention of these considerations.20

Such extreme legislative deference in the workers’ compensation context is disheartening.

IV. Conclusion

Hensley leaves the door open to future as-applied challenges. Practitioners should look for:

- workers with Class 1 impairments to multiple body parts;

- Class 1 impairments with greater than Class 1 factors;

- “Classless” impairments; and/or,

- “more significant” Class 1 impairments. Finally, there may be a Due Process challenge available based on the analyses in the Hensley dissents. Regardless of the facts or legal theory in the next challenge, overcoming rational basis review will be a significant hurdle.

END NOTES

- Caldwell v. MACO Workers’ Compensation Trust, 2011 MT 162, 361 Mont. 140, 256 P.3d 923.

- Goble v. Mont. St. Fund, 2014 MT 99; Satterlee v. Lumberman’s Mut. Cas. Co., 2009 MT 368; Caldwell v. MACO Workers’ Compensation Trust, 2011 MT 16; Reesor v. Mont. State Fund, 2004 MT 370, et. al.

- Hensley at ¶ 29

- Hensley at ¶ 40

- Hensley at ¶ 18

- Hensley at FN 10 (emphasis added).

- Hensley at ¶ 11

- AMA at App. A, 604; Id. at § 2.2c-2.2d, 22-23.

- AMA at ch. 14

- Id. at ch. 15.4c

- Id. at ch. 11.2

- §1.8c(1).

- App. 47 at § 1.8c(3).

- § 39-71-711(1)(c); Hensley at ¶ 11; Guide §1.8c

- Hensley at ¶¶44-108

- Hensley at ¶¶109-135

- Caldwell v. MACO Workers’ Compensation Trust, 2011 MT 16; Reesor v. Mont. State Fund, 2004 MT 370, Henry v. State Compen. Ins. Fund, 1999 MT 126, 294 Mont. 449, 982 P.2d 456, et. al.

- 2011 MT 45.

- Stratemeyer v. Lincoln Cty., dissent, 259 Mont. 147, 155–56, 855 P.2d 506, 512 (1993) (Trieweiler, dissenting).

- Hensley at ¶40 w

What would your practice be like without MTLA?

You could find all the auto insurance coverage going toward your client’s medical bills while his health insurer pays nothing. You could be hiring experts to help you apportion the damages attributable to your client not wearing her seat belt. You could be calling all your colleagues, one by one, day after day, trying to find out if anybody had any experience with, depositions of, or information on the defense medical expert that is about to examine your client.

Increasing your membership level helps assure that MTLA continues its legislative work, provides listserve access to the collective expertise of all MTLA members, and so much more.